Back

Back

Fish weirs: as irritating as traffic-

(Newsletter No 4 Autumn 2002)

Documentary Research;

If you’ve ever been tempted to play skittles with motor-

Whether this is the exaggeration of vested interests or not, what is undeniable is

the strength of feeling these contraptions engendered. So why go to the trouble and

expense of constructing weirs (the Admiralty report notes the total length of one

as 400 yards) with such fierce opposition a certainty and demolition a possibility?

A statement from one defendant (in the dispute alluded to previously) suggests poverty

was a driving force. John Cory Chichester stated that he had six children and “nothing

to depend on but the weir”. Another explanation is the age-

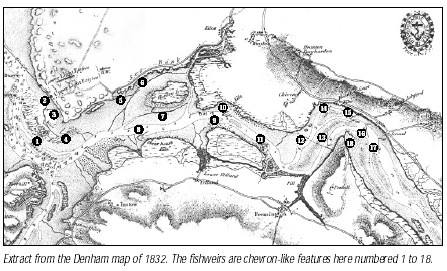

Lieutenant Denham’s chart commissioned in response to the fish weirs dispute, shows

some eighteen weirs marked on the Taw/Torridge estuary. The aim of the NDAS field-

Enough examples have been located to make measured survey the next priority. This has already been achieved at Crow Point and useful sketches have been made at other sites. Survey at Horsey Ridge has been problematic (at present the substantial remains are largely sanded over again), but hopefully this can be recommenced at a future date, as the size and construction phases offer interesting possibilities of interpretation. Fieldwork is also being focused on parts of the estuary outside the remit of the Denham chart. References have been found to fish weirs at Umberleigh and (unsurprisingly) at Weare Giffard. In addition, there are a number of structures along the Torridge near Tapely Park, at Northam Burrows and at Instow which, despite similarities to weirs, may be jetties, wharves, slips or structures related to shellfish harvesting. Furtherresearch is needed. Addirionally, aerial photographs are being investigated (stunning results were achieved at Whitstable Bay in Kent using this resource) and living history (a tape of Appledore fisherman Sid Crick) has yielded some interesting observations on sluice gates at Horsey Weir. There is also the evidence of old photographs and paintings. For those who have

trouble imagining a fish weir, a 1795 painting by William Payne reproduced in Alison Grant’s books, shows a weir at Coolstone, Instow. The weir at Lynmouth (to the right of the Rhenish Tower), used until recently, albeit a coastal rather than an estuarine example, is well worth a visit, being one of the best preserved in the area. It is hoped that, weather allowing, survey of some of the extant weirs will be possible this autumn and next spring.

Fish weirs Update: Chris Preece (Newsletter No 5 2003)

Taking advantage of the high tides of the 20th March and some unseasonably clement

weather, a small but determined group of NDAS volunteers set out to survey weir number

11 on the Taw, namely Allen’s Rock. The stakes were first located and marked (with

a small piece of masking tape) and then offset measurements taken from a base line.

The tape was removed after each measurement thus ensuring that no stakes were omitted

in the survey. A total of eighty measurements were recorded and are in the process

of being drawn up. Given that the return could not be located (even with the aid

of a reluctantly wet-

It is hoped that further survey will help to identify the weir most likely to be informative in regard to C14 dating, so please, more volunteers! The next survey dates are in this newsletter.

The previous day I had managed to locate the elusive weir 9 at Lower Yelland (elusive

possibly due to the fact that the proximity of the Boathouse Inn on a prior jaunt

had proved more of a draw than further mud-

Documentary research in Northam has turned up a reference to Captain Whyte, a fervent abolitionist of fish weirs. An 1842(?) edition of the Gazette refers to his list of the weirs that ‘have desisted from fishing and the hutches that have been destroyed on the Torridge, without hardly a murmur’. Colonel Whyte, the Gazette tells us, was anxious that the Taw should be equally free, but, the Gazette continues, ‘we would advise him to cease his thankless labours’! However unappreciated Whyte’s efforts were at the time, his list, which is quite specific about places, provides further material for research.

Fishweirs Update 2 -

We stood in disbelief. No gale, no hail, no horizontal rain, no driving wind or bitter

temperature -

On both Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th September we assembled at Horsey Ridge, Braunton Marsh (no. 7 on the Denham chart of 1832) and quickly shuffled off our thermals, pullovers etc., delighting in the unseasonably clement weather.

Horsey Weir is very large, but is variably visible owing to movements of the sand ridge. On the Saturday, Terry, Alistair and myself were tasked with determining the present extent of visible remains, cleaning seaweed from the stakes and revealing those stakes which we suspected were concealed. Our assumptions regarding the apex of the weir were challenged when we found three large posts running off obliquely from the main line of posts. These may represent a gate or sluice or even possibly a basket/funnel structure. In this regard, an extract from an interview with Sid Crick (Appledore fisherman, born 1913) by DArcy

Andrew is revealing.

Interviewer: And you said that the Horsey Weir had two gates which opened with the tide?

S.C.: Opened at the tide and closed on the ebb. Thats how it used to work.

Interviewer: And so there’d have been quite a nice pool of water there?

S.C.: Oh yeah, there would’ve been -

On Sunday, Mary Cameron (a veteran of the Allens Rock survey), new member David Grenfell

and myself were joined by Barry Hughes, of Appledore Maritime Museum, who arrived

in appropriate style by boat, mooring up just down from the weir in the narrow creek.

We followed a similar routine to that used previously, namely marking all visible

stakes with masking tape (subsequently removed in sequence), setting up a base line

and using offset measurements to record (the drawing up can then be done later).

Slack water gave us a good window of opportunity, and we were able to work from 12.30

until 3.30pm. On the north side, a central line of stakes with evidence of wattle

was apparent, presumably the earlier phase of build. Two external lines of posts

with a rubble in-

Seventy-

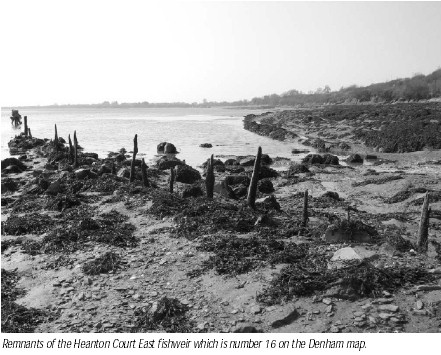

Fish weirs update 4 -

It is hoped that the fishweirs project will be concluded by the end of the year with academic publication, dissemination in a format more suited to the general public and C14 dating all needing discussion and agreement by the NDAS committee.

In terms of survey there only remains the south side of Horsey Weir to complete, but given the size of this structure and the shifting sand cover, more than one visit may be necessary. Three suitable early dates are the 5th and 6th of May, followed by the 4th June. Volunteers please contact me on 01237 475368 (otherwise conscription may be necessary!). Recording of Horsey will mean that three weirs of varying types will have been drawn to scale; an essential means of comparison with other published examples.

Following the reference in the Spring 2003 newsletter to a list of weirs on the Torridge (Bideford Weekly Gazette 1862), the observant and unremittingly enthusiastic NDAS member David Grenfell called me regarding stakes in the river bank near Landcross. Three of us (David, a badly trained dog and myself) went to investigate and returned more confused than when we set out. A dizzying array of stakes was visible; some straight lines angled from the top of the bank, some curved on the bend in the river and some encroaching towards the middle of the channel.

Whether some or all were connected with fish entrapment is difficult to ascertain, but research in Northam has suggested that fish traps took many forms. Articles in the Bideford Gazette refer to fishing mill dams, fishing cruives, weirs, hutches, coops and fenders as well as the incongruous ‘privileged engines’. Given the use of nets and rod and line as well, it is not surprising that an editorial of 1860 in the Gazette describes fishing as a “war of extermination” and decries the “murderous system pursued here”.

Competing interests in a hierarchical society meant that while the Salmon Fishery

Acts 1861-

A Final Word on Fishweirs -

Last year, at one of the evening talks, Chris Preece gave a fascinating presentation on the fishweirs of N. Devon, following which 'five went fishing' to assess the fishweir situated in the channel between Crow Point and Appledore.

Needless to say, being NDAS members, led by Ann and Chris Mandrey, we chose the coldest, windiest, bleakest day in March to coincide with the lowest tide of the season. The excitement of that day was later discussed with a friend Paula, studying marine biology, who proceeded to tell me that one Valerie Robson used to live in Lynmouth, where her father owned the fishweir in the estuary there. To cut a long story short, Valerie had not only been her father's regular assistant, but also had the foresight in 1993, to video the weir after it had been sold, while still in working order.

The video was duly shown to a very interested NDAS audience in November, when Valerie complemented the scenes from Lynmouth with a fascinating insight into her childhood memories spent at each tide change, clambering over the rocks to recover the salmon, trout and, in season, white bait, which were then sold to the local hotels.

The weir was fished from April to August. A further custom instigated to allow the salmon to run up river to spawn, was the practice of opening the sluice gate on the Friday tide until the first tide on Sunday.

The weir had been in Valerie's family, the Bevans, for three generations, and was previously owned by the Lords of the Manor from the early 1700s. The oak uprights were interwoven with silver birch brushwood to contain the fish at turn of tide. To catch the fish in a scoop net necessitated the family working around the clock. Sometimes, finding their way over the boulders at nighttime proved difficult until Mr. Bevan painted each rock along the route with Valerie according each one a name, e.g.Cheddar Gorge!

Obviously during the spring tides and winter storms, these structures where dislodged

and carried away down the coast. Regular maintenance was required to replace the

brushwood, especially after stormy weather. The flood damage in August 1952 almost

destroyed the weir, when the over-

Since Mr. Bevan's death, the weir has been managed locally. However with labour difficult to find, and fish stocks depleted, the Environment Fisheries Agency recently purchased the weir.

Valerie had invited Rob Jones from the Fisheries Agency to our meeting, where we

were all extremely pleased to hear that a decision on the weir had been reached.

The weir was to be renewed to the original design, using chestnut instead of oak

posts. The work was just awaiting a risk assessment before the task was to be under-

Our thanks go to Valerie for such an informative and personal talk, to Chris for

our discussion, and to Rob Jones for sharing the Environment Agency's plans and problems.

It was like watching history in the re-