Back

Back

Parracombe Project: Holworthy Farm -

(Newsletter No 4 Autumn 2002)

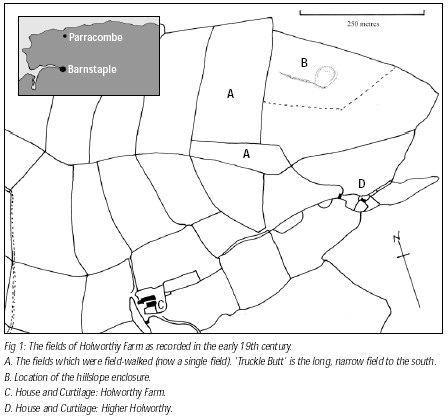

Holworthy Farm, belonging to Phil and Julie Rawle, lies in a combe to the south-

Since the last newsletter, the Parracombe project has made further progress, in that

the investigation of Holworthy Farm is now properly under way. On the 19th May, Society

members and volunteers from Parracombe met at Holworthy Farm to field-

This site, which is not scheduled, represented an opportunity to investigate by excavation

a possibly prehistoric element of the landscape. In order to help with funding, our

fund-

On 15th July -

The only datable finds from the three trenches were two sherds of medieval pottery

from the topsoil and a small number of flint beach pebbles, some with a preparation

flake removed. These might be thought to represent mesolithic activity. On the face

of it, the evidence which we recovered leads to no clear conclusions. The huge amount

of weathered stone in the structure suggests the result of initial ground clearance

ahead of cultivation. The lack of a ditch was unexpected, but as the enclosure appears

to be built of stone, like a ring-

The next step at Holworthy will be to examine the site of Higher Holworthy. This

separate holding was listed in the 1840 tithe apportionment, and on the tithe map

two buildings are represented together with a garden. On the site now are only the

garden enclosure and the ruins of a barn. Of the house there is no obvious sign.

It is said that before the 1952 flood there was a pack-

Fieldwork, Summer 2003: (Newsletter No 5 2003)

Parracombe

The first priority this summer is to continue with our investigation of the Parracombe

landscape. At Holworthy Farm, where we began work last year, we intend to conclude

our survey by recording the field-

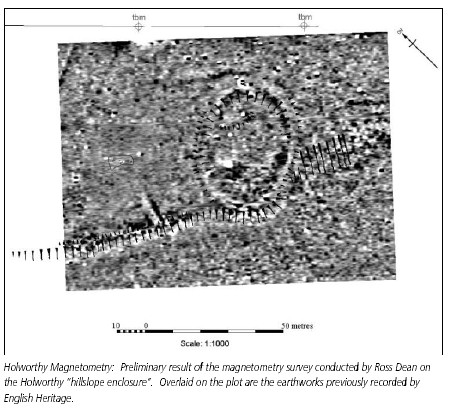

During March Ross Dean conducted a magnetometry survey on the hillslope enclosure with very interesting results. These have encouraged us to plan a further excavation on the enclosure this July. By the end of the year, therefore, we shall have data from a variety of surveys as well as from excavation, which will enable us to begin to understand landscape development on this fringe of the parish.

From Holworthy, we shall move to the other side of the parish to West Middleton Farm.

Having previously surveyed the field-

This summer, therefore…

The first requirement is to do the field-

We propose, therefore, to undertake a further excavation on the enclosure this year. This will take place during July and will last a week. Proposed dates are Monday 14th to Saturday 19th July, but contact Colin (01271 882152) to confirm this. Work at West Middleton will begin in late summer. Phone Colin for details..

Parracombe Project: Holworthy Farm 2003-

Field Boundary Survey:

As proposed in the Spring 2003 NDAS Newsletter, a field-

Preparations for the survey

In the 19th century William Smyth described the farm as poor and this may account

for the less elaborate treatment of the boundaries. Another clear difference is the

presence of a number of corn-

On the cultivated side the bank presents a sloping face. The purpose is to discourage

animals from straying from the common onto cultivated land, and to make it easy to

chase them out if they should somehow get in. A corn-

Excavation:

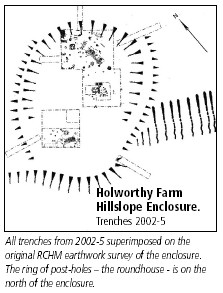

In the previous newsletter, members will have seen the preliminary results of Ross

Deans magnetometry survey of the Holworthy hillslope enclosure. Further tweaking

of the image brought into focus features that Ross recommended for close examination.

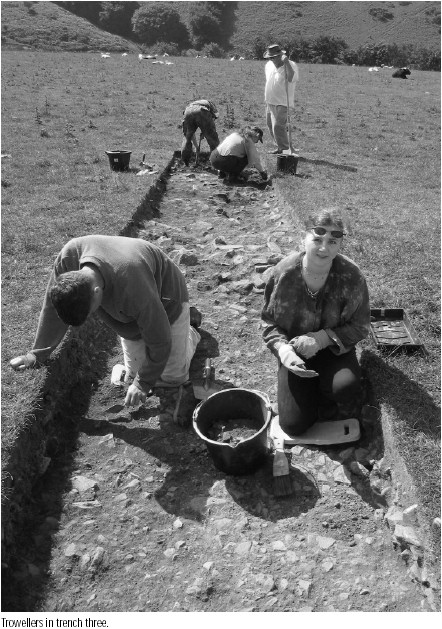

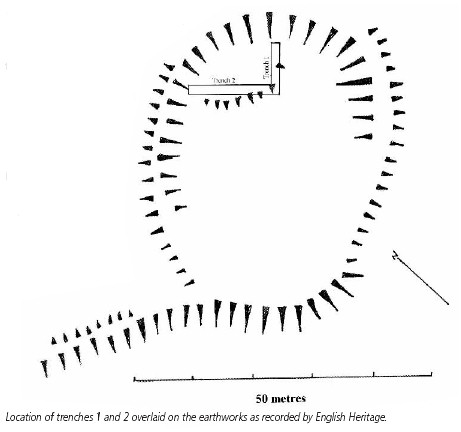

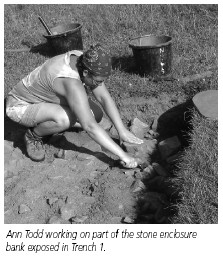

Excavation began on 14th July. With the magnetometry as a guide, two trenches were

pegged out, one of 8.5m x 1.5m running north-

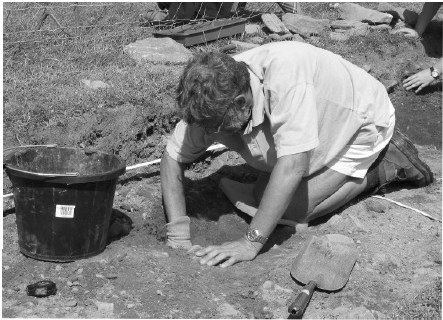

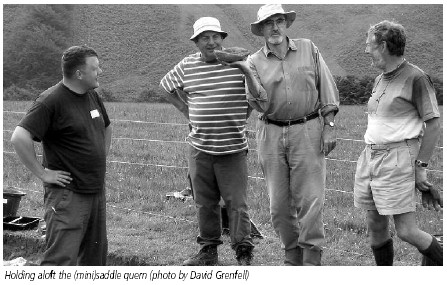

Recording a post hole at Holworthy

In the process of exposing the stone layer in Trench 1, specifically in the area

where the two trenches met, a number of flint flakes and small thumbnail scrapers

were found. These were the first evidence we had that might point to a prehistoric

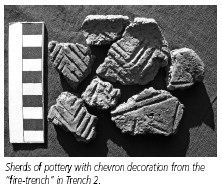

date. More was soon to come, however. In the central section of Trench 2, the stones

lay less densely and plough-

This exciting discovery came on the second day. On the third day came the rain and the scuppering of any plan to complete the excavation in a week. In the end we spent sixteen days dodging between the spells of rain in the wettest weeks of an otherwise glorious summer! Nevertheless, our small, but reliable team worked on manfully.

In Trench 2 a broad band of heavy stone was exposed lying at right-

After heavy rain had flooded the lower part of the excavation, the area where the two trenches met was suspiciously slow to dry out. This was where we had seen most of the flints and where a number of large stones protruded though the ‘metalled’ surface. Consequently a 1.5 x 1.5 metre excavation was carried out here. Beneath the layer of small flat stones and gravel, a gulley was revealed which was filled with charcoal stained soil. The large stones lay in this gulley, and when they were removed, charcoal, including pieces big enough for species identification, was found beneath them.We cannot be sure, but the gulley, which was about 30 cm wide and 15 cm deep, seemed to show a curvature and may be part of the drip gulley of a round house. Alternatively it may represent a drain. Within the charcoal stained fill was one abraded sherd of BA pottery and one flint flake.

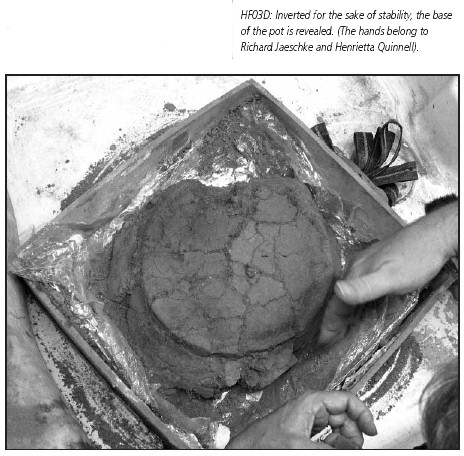

The pottery in trench 2 having been left in place until we were ready for it, the

intention was to lift it in a block. Taking advice from professional conservators

Richard and Helena Jaeschke, we excavated around the mass down to bed-

The Society owes its thanks to all those who helped with the excavation. In particular,

lifting the pot was a great success, and I must thank Alistair Miller, Roger Ferrar,

Derry Bryant, Janet Daynes and Gordon Fisher for their valuable efforts. Thanks are

due also to all who assisted in the dig; once again the co-

This year’s excavation had its difficulties, but nevertheless our small, but reliable team gathered enough evidence to raise questions that need to be answered by further excavation in the future.

Field Boundary Survey at Holworthy Farm: The Results -

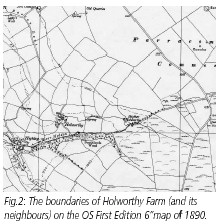

In previous editions of the NDAS Newsletter there have been several references to

the fieldboundary survey being conducted within the Parracombe Project. The aim of

this activity is to ascertain whether it is possible, through objective analysis

of the features of the very prominent hedge-

The development of such a tool falls within the research priorities highlighted in the recently formulated “Historic Environment Research Strategy for Exmoor” (Objective 8.i). To date nearly 300 boundaries have been recorded on East Middleton and Holworthy Farms. Now the data collected have been ‘crunched’ and some patterns have emerged. What do they tell us at Holworthy Farm?

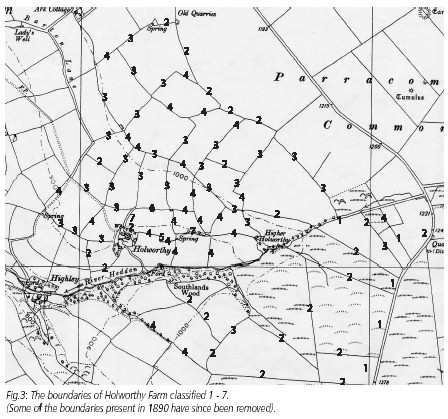

At Holworthy 117 boundaries or boundary segments were recorded. The data recorded

for each boundary include width through the base, width across the top, height from

the ground on both sides, presence or absence of stone facing, style of facing, shrub

and tree species present, evidence of hedge management, topography and relationship

to other boundaries, watercourses, trackways or farm buildings. On the basis of the

oft repeated remark, “You have to respect the work that went into these boundaries”,

it seems obvious that the quantity of material mounded up to make a hedge-

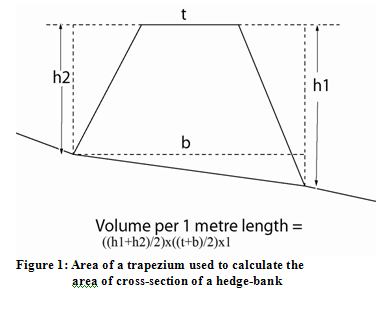

Measuring width at base, width at top and height gives the dimensions of a cross

section which is essentially a trapezium the area of which is given by the formula

h x (b+t)/2 (where h = height, b = base, t = top). As few hedge-

If we now apply this numerical classification to a map showing the boundaries of Holworthy Farm, patterns begin to emerge. There are few boundaries which are consistently of one class; what appears to be a single boundary can be a class 3 at some part(s) of its length and a class 4 at others. There is only one instance of a 2 juxtaposed to a 3. There is no example of a boundary being both a 2 and a 1. The 2’s and 1’s are restricted to either the boundaries which postdate the tithe map of 1840; or they are cornditches at the outer limits of the land that was enclosed before 1840. In addition they include one boundary which was present in 1840, but which, for certain reasons, is suspected to be a relatively late addition. The 3’s and 4’s are therefore characteristic of the land which was enclosed before 1840. The number of 5’s, 6’s and 7’s is very small and is restricted to the land closest to the farm buildings. It begins to seem, therefore, that there is a group of slighter boundaries characteristic of recently enclosed land and a group of heavier boundaries associated with older enclosed land.

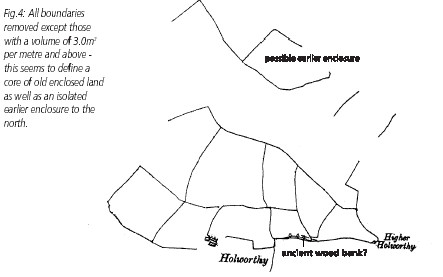

If we now split up Class 3, consigning its lower end (2.6m3-

Does the analysis of field boundaries contribute anything new, therefore? Well, yes.

It not only provides a physical complement to retrogressive map analysis, but can

also spring surprises. Holworthy provides two examples. Firstly, to the north of

the early core of Holworthy land were formerly three fields (now two) which in the

Tithe Apportionment are named West, East and Higher New Ground.West and East have

slighter boundaries than those in the core, but Higher New Ground stands apart, having

heavy hedge-

Finally, on the subject of hedgerow species, people who know of the so-

From the Bottom Up: Restoring the Holworthy Pot -

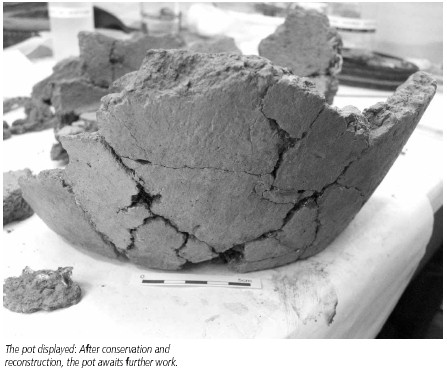

From pictures taken and descriptions provided before the pot was removed from the ground, we already had a good idea of the nature of the object. Nevertheless there’s always an intense amount of examination and discovery when an object first arrives at the conservation lab. In this case the object arrived from the excavation boxed in its soil block and protected in a plaster case. Our first move was to invert it, place it on a padded surface and carefully remove soil to reveal the base and assess its condition.

After several thousand years in a wet, acidic environment, the ceramic was very fragile. This is usually the combined effect of the clay having been fired to a rather low temperature and the dissolution of some of the temper used in its manufacture. If the pot had been allowed to dry out, the ceramic could have shrunk and crumbled away. To prevent this, the wet ceramic needed to be consolidated with a resin which provides strength as the water evaporates. The resin must be able to penetrate the ceramic evenly and remain stable, without changing colour, size or strength. For preference it must also be easily removable in future. Fortunately an excellent stable resin is available: Primal WS 24 is a colloidal dispersion of an acrylic resin, which can be diluted with distilled water for application, and which is soluble in acetone when dry. This solution was used on the Barnstaple kiln which was excavated in 1988 and is displayed in the Museum of North Devon.

As the soil was removed from the base, it was possible to see the nature of the surface

on which the pot had been placed. Stones were found touching the base and sides,

as though it had been laid on a stony surface, possibly in a stone-

The pot was then turned right way up and supported while the soil inside was removed and put in separate bags for later examination. The only evidence of the vessel’s use was a dark ring visible on the outside of the base. Consolidation was continued as each new area was exposed. When all the soil had been removed from the surfaces of the pot and the consolidated ceramic had dried, the individual sherds could be cleaned with swabs of acetone.

Although many of the fragments were in situ when found, they were separated by soil and roots which had to be removed before the pieces could be reattached. The cleaned sherds were joined together using a viscous solution of Paraloid B72, an acrylic copolymer resin. The stray sherds which had been separately removed from the ground were treated the same way, but were carefully numbered to show their original positions. Some joins were found between the sherds, but few could be found to join the actual pot. This was frustrating as these sherds included a fragment of rim and some decorated with diagonal parallel incisions.

Once the main pieces had been joined, some gapfill was necessary to give the pot sufficient strength to withstand handling and display. The edges of the gaps which would be filled were protected with a thin layer of Paraloid B72. The gaps were then filled with Polyfilla, a commercial blend of plaster of Paris with cellulose powder. This was shaped and then painted with powder pigments mixed in a solution of Paraloid B72 in acetone to provide an overall match which can clearly be distinguished from the original. It is hoped that future work may enable more joins to be made and the rest of the pot to be rebuilt.

The reconstructed pot is now on display in the Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon.

Summer 2004 Excavations at Holworthy Farm -

(Newsletter No 8 2004)

On 19th July 2004, 20 volunteers including members of NDAS and of TAG as well as four students from Exeter University gathered together at Holworthy Farm, Parracombe to begin the season’s excavation on the Holworthy hillslope enclosure. The weather was benign, tented accommodation had been provided by RMB Chivenor, portaloos had arrived, the proposed trenches had been mechanically deturfed and sheep and cattle were kept at bay by a very effective electric fence. This year we were employing a site supervisor in the person of Dr Martin Gillard of English Heritage and Exeter University who freelances as an excavator. Martin brought with him four student volunteers from Exeter, Sam, James, Nick and Flick (Felicity!) who were comfortably accommodated in a barn at Walner Farm. In addition, Martin’s partner Genna had baked a cake which was ceremonially doled out with a (clean) trowel at the first morning teabreak.

Things were off to a good start and in general were to stay that way. Since the 2003

evaluation trenches had turned up evidence of Bronze Age occupation, the plan for

2004 was to open up a larger area so that the pottery and gully feature previously

exposed could be seen within a broader context. In addition we wanted to explore

the nature of key features of the site highlighted by Ross Dean’s magnetometry 5

survey. This meant open-

The Excavation:

Ross Dean had previously been over the site with resistivity and gradiometer surveys

and worked up the data into very readable colour-

Trench 1 was laid out 12.0m x 1.5m E-

Trench 2 was an open area laid out 10.0m x 10.0m in the NE quadrant of the enclosure. The purpose of this was to pursue the implications of the Middle Bronze Age pottery vessel and of the length of gulley filled with charcoal and charcoal stained soil found in 2003. This area lay across a slight platform which had been previously identified by earthwork survey and which included possible areas of burning activity identified by the geophysics.

Trench 3 was laid out 12.0m x 1.5m to the NE of Trench 2. Like Trench 1, the purpose here was to explore the linear feature identified by geophysical survey and to ascertain its relationship to the enclosure.

Trench 4 was laid out 4.0m x 4.0m at a distance of 30.0m NW of Trench 2 in an area where geophysical survey had indicated a number of linear features which suggested small rectilinear enclosures, possibly ditched or fenced paddocks or small arable fields. In addition the linear feature to be explored in Trenches 1 and 3 also reached this far and crossed the edge of one of the “enclosures”. The purpose here, therefore, was to examine this junction of features.

The Results:

Trench 1:

After removal of the turf and ploughsoil, a 1.5m – 2.0m wide band of densely packed

stone was revealed lying N-

Trench 2:

Trench 2:

This large area was the most revealing. Removal of the turf and initial mattocking

of the ploughsoil revealed a broad and quite dense spread of stone such as had been

seen in previous years. This was concentrated towards the NE of the area, becoming

less pronounced to the SW. A few sherds of prehistoric pottery were recovered. Successive

campaigns of mattocking and trowelling finally removed the overburden of ploughsoil

and stone spread, revealing a predominantly orange subsoil with a great deal of embedded

stone. The section of gulley revealed in 2003 which had been thought perhaps to represent

a drip-

A considerable number of post-

Trench 3:

Features found in Trench 3 were very similar to those seen in Trench 1, ie. a band

of densely packed stone, a band of random stone and a scoop where the hilllside had

been dug intoapparently to form a scarp and a platform. As in Trench 1, a box-

Trench 4:

This 16m2 area was meticulously excavated by Sam Wells, one of the Exeter students.

The identified features included a single large posthole in the W corner of the area

which was stonelined and ‘capped’ just like those in Trench 2; a spread of random

stone like that seen in Trenches 1 and 3; a line of stake-

Provisional Conclusions:

-

-

-

-

-

– in the form of a large round-

-

-

The single post-

Possible Future Work:

-

-

-

-

With so much burning activity on the site, we have a lot of charcoal from which to select samples for species identification and Carbon 14 dating. In addition we have numerous bulk samples taken from different contexts which need to be treated in order to extract possible environmental evidence. Treatment means wet sieving and sorting by flotation. This is a wet and probably chilly job, but has the potential to be very rewarding. Physically separating environmental treasures from soil and clay is a job

for volunteers. Any offers? Please contact Alistair (01598 740359)

Higher Holworthy

While we were digging on the hillslope enclosure, Jim Knights took a party of volunteers

down to the abandoned site of Higher Holworthy in the valley below. This small settlement

was shown as inhabited at the time of the Tithe Survey (1840’s), but was deserted

by the time of the 1851 census. In the 1840’s it was a separate holding from Holworthy

being occupied by Thomas Dovell. All we see now is an irregular enclosure, a ruined

barn and some struggling apple-

The following bodies helped NDAS to fund the Holworthy Excavation in 2004:

Council for British Archaeology: £500

Exmoor Trust: £200

North Devon District Council (Community Grants): £684

Royal Archaeological Institute: £1200

The Holworthy Project: Progress and Plans -

(Newsletter No 9 2005)

During the winter, examination of material recovered in the excavation at Holworthy Farm in 2004 has thrown up some very gratifying results.

As I indicated in the last report, we were able to recover a considerable amount of charcoal from various contexts which meant that we had organic material which could be Carbon 14 dated. The process is based on the fact that all living things absorb, during their lifetime, the unstable isotope of carbon, carbon 14, from their environment. On death, no more is absorbed and what is present at that point begins to break down to a more stable form of carbon. Carbon 14 decay proceeds at a known rate, so that measurement of the proportion of the isotope remaining in, for example, a lump of charcoal, provides a measure of time elapsed since the wood was cut. It’s not quite so straight forward, as the concentration of Carbon 14 in the environment has varied over time, so that raw dates have to be adjusted or ‘calibrated’. Dates are given as BP ie. Before Present where Present is conventionally 1950.

Four gross samples were selected for examination, one from a deposit of burnt material

beneath the stones forming the enclosure bank (108), one from a small scoop which

contained pottery sherds and charcoal (215) and one from the gulley or trench which

snaked through the roundhouse site and had a charcoal-

We have also been able to make some deductions about the Bronze Age environment of the site. From the identification of the charcoal we can say that oak, hazel and willow (presumably sallow or goat willow) were present in the vicinity. Further clues have been provided by pollen recovered from the fill of the gulley. A ‘tinned’ sample was sent to Heather Tinsley of Bristol University who reported that, although the pollen preservation was poor, she could identify oak, hazel, alder and pine, thus adding to the picture of the Bronze Age tree cover. Among herbaceous species she identified principally dandelion, ribwort plantain, daisy and buttercup suggesting disturbed ground around the site, and heather, grasses and fern suggesting an open, grassland environment. She also found roundworm eggcases, which could have come from pigs, but more likely came from people. Heather also found some cereal pollen, which fits nicely with the most recent discoveries.

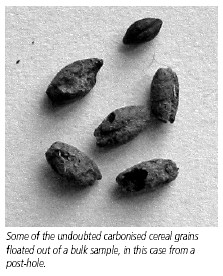

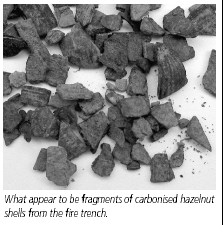

Before we left the site last summer we took bulk samples (40 litres at a time) from a number of contexts. These were to be sorted by flotation in order to extract any organic material, most likely charcoal fragments and other carbonised matter. For this we needed a flotation tank, but did not possess one. Asking around got us nowhere, so we had to provide for ourselves. To this matter David Parker set his mind and manufacturing skills, and, with the generous provision by Alpharma of Whiddon Valley of an empty drum and fine mesh, he succeeded in building a very useful piece of kit (see the accompanying article) with which to treat our samples. At David and Judy Parker’s house in Ilfracombe, a number of Society members spent several cold Saturdays processing the material and ending up with quantities of ‘flot’, the organic matter floated out. During the last couple of months, David has dedicated himself to sorting this material under a binocular microscope (lent by the Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon) and has succeeded in extracting quantities of carbonised seeds, fragments of hazel nut shell and plant fragments. None of these have yet been submitted to a specialist for identification, but among them are undoubted cereal grains, probably barley and emmer wheat, nicely complementing the cereal pollen found by Heather Tinsley. This is the first direct and positive evidence for prehistoric cereal cultivation in the Exmoor area, a first for NDAS!

Finally, the carbonised wooden object, which was discovered beside the fire-

In July this year we are planning to return to the site, probably for the last time.

Starting on 4th July, we intend to excavate between 140 and 200 square metres inside

the enclosure. The objectives will be to examine a geophysical ‘hot spot’ identified

by Ross Dean, to examine the area below the edge of the house-

Finally, at the end of the main excavation period we shall be holding an Open Day at the site for NDAS members and the people of Parracombe. This will be on Sunday 17th July from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. If you don’t know the site, there will be signs on the approach roads pointing you in the right direction. You will be asked to park on the roadside at SS 689445, from where you have a walk of about 400 metres downhill across grassland. I must point out that we are on private farmland and must, of course, observe all the usual countryside rules about shutting gates.

Members Interest Articles:

The Landscape Context of Holworthy Farm: Chapman Barrows , Hazel Parker ( Newsletter No 9 2005)

An A-

Holworthy Farm Excavation, July -

Following the very successful NDAS Holworthy Farm excavation of 2004 – reported in

previous newsletters -

Permission and approval were obtained, as before, from Phil and Julie Rawle, Rob

Wilson-

Derry Bryant took charge of funding, and was able to raise a total of £2,000 from The Royal Archaeological Institute, the Council for British Archaeology and North Devon District Council.We are grateful to these bodies for their support and must also thank RMB Chivenor once again for the loan of tents. Special mention must be made of Jim Knghts who was a logistical Mary Poppins, always seemingly able to come up with just what was needed!

The excavation was set for the two weeks from 4th to 17th July 2005. There was to be an open day on the final Sunday, 17th July. A barbecue was arranged for volunteers on the middle Saturday at Walner Farm., and we are once again grateful for the hospitality of Phil and Jean Griffiths.

The Excavation:

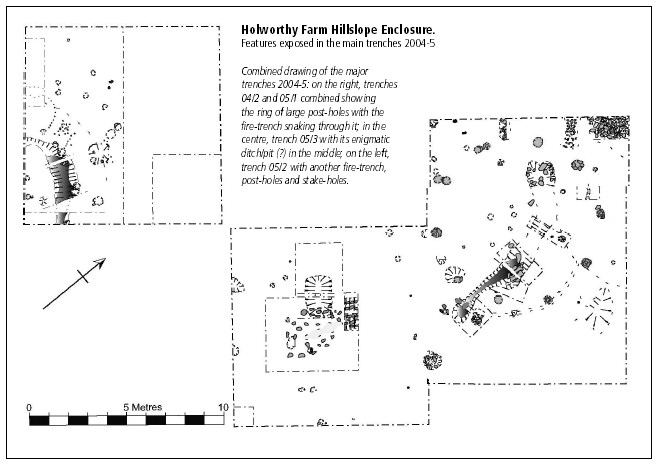

The site was prepared during the last week of June, when three trenches were pegged out. Trench 1 was laid out 10.0m x 4.0m immediately to the NW of Trench 2 of 2004. Trench 2 was laid out 10.0m x 10.0m in the SW quadrant of the enclosure. Trench 3 was laid out 10.0m x 10.0m on the S side of the enclosure adjacent to Trench 2 of 2004. Ross Dean surveyed the trenches into the overall site plan.

When the excavation began on July 4th the team was initially divided between Trenches

1 and 3, work on Trench 2 not beginning until the ploughsoil had been hand-

Initial Results:

Trench 1:

The major post-

Trench 2:

The stated purpose of Trench 2 was to locate and examine the context of a large geophysical

anomaly identified in Ross Dean’s magnetometry survey of 2003. The initial plan to

excavate 100m2 was trimmed back largely because of the unexpected depth of the ploughsoil

in this part of the site. By reducing the area by 50% efforts were concentrated on

the SW half of the area. In the deep, relatively humus-

Trench 3:

This trench, the purpose of which was to see what might be happening in the centre

of the enclosure, turned out to be relatively devoid of features, but presented some

puzzles. There were a number of holes which might have been post-

Around 50 large and small soil samples were taken, most of them containing organic matter which we hope will provide additional dating and/or environmental evidence. To date the examination of the “flot” resulting from flotation has identified a substantial number of cereal grains together with fragments of chaff which suggests processing on site and probably the growing of grain nearby. Identification of other organic remains awaits specialist attention. There is a lot more work to done on the samples. Anyone wishing to volunteer their assistance, please phone David Parker on 01271 865311.

We may conclude at this point that we have identified this hillslope enclosure as a Middle Bronze Age settlement surrounded by a substantial stone bank within which there was at least one major building. Cereal crops were grown nearby. The settlement was abandoned around 1000 BC. The features of Trench 2 offer a tantalising glimpse of activity and it is tempting to pursue the evidence in the direction of the enclosing bank, in the shelter of which most activity on the site appears to be concentrated. For the present however, it is necessary to consolidate what has been achieved.

Holworthy Farm Update Terry Green

(Newsletter No 11 2006)

After four seasons of excavation at Holworthy Farm we are at the point where we either

continue and turn it into a long-

At present all of the Holworthy pottery has been marked up and has been to Henrietta

Quinnell so that she can estimate the work involved in writing a report. The single

mass of sherds that came from our second “fire-

Meanwhile all the context details have been assembled on a data-

As indicated above, since the last newsletter, the wet-

Furthermore the grain was concealed beneath a flat stone in the base of the hole. As for wood, identified species include oak, hazel, willow, hawthorn, ash, birch and alder. The wooden bowl or platter (?) excavated in 2004 was of oak. Among the 21 charcoal samples that we have had identified, oak and hazel are by far the most frequently occurring, as one might expect, but ash occurs only once. This is interesting when you consider that ash is a very common tree in the local landscape today and that it makes very good firewood. I have recently discussed this with Dr Judith Cannell, an expert on woodland archaeology, who suggests that ash flourishes in open conditions such as hedgerows, which were probably not a feature of the local Bronze Age landscape.

With the financial support of Exmoor National Park, the samples for radiocarbon dating

were sent to Glasgow in February. The results, which have just come back, help to

tighten the date range for the features of the site, currently homing in on 1300

-

For the purposes of writing up and interpreting the site, we need to be able to place it in both a broad regional setting and in a local context where funerary monuments such as Chapman Barrows are a major feature, but nearby settlement remains on South Common are possibly more meaningful in terms of landscape development. For the purpose of such interpretation, we need to return to the Parracombe Project which got somewhat sidelined when Holworthy came along, but which offers a way to assess the landscape as a whole.